Oh, we talked about it, on and off for a week. We’re still talking about it. One of us will mention it the same way you might say, “But… that dog… driving that car…” pronouncing your words slowly, with the far-off gaze of a person with a tenuous grip on sanity. Sitting in the salmon-colored clamshell booth at Pamplemousse Grille—a soft room so perfectly earth-toned it feels like you’re having ahi towers in a comfortable archeological dig, or in Fort Lauderdale circa 1990—we try to clean the menu with a napkin. Maybe some stray bit of duck confit was making a 1 look like a 4.

But, no. There it is. A $44 grilled cheese sandwich. With lobster and truffle, admittedly. But I mean, c’mon. Finding a sandwich over $40 is a bit like stumbling on a million-dollar Chevy.

I’ve been in some fancy restaurants that smelled of grand cru and lightly simmered net worth, but this carbohydrate Hope Diamond has me flustered. Do I order it directly through the server, or does Sotheby’s have to process this one?

Taking On the $44 Grilled Cheese at Pamplemousse Grille

Korean beef

I couldn’t bring myself to order it the first night. I heard a small scream from the vicinity of my wallet and got cold feet. I had to think about this sandwich, and maybe the meaning of life.

“Almost seems like a gimmick,” I tell my fiancée back at home.

“We have to order it,” she says.

“We will. Let me sleep on it. I’m processing, and there may be a little grief involved.”

By the next morning, I start to rationalize the grilled cheese. “I bet it’s a full lobster in there. A whole tail, plus fresh Périgord black truffle shavings, would be worth $44. It’s basically a lobster dinner. I bet he’s just calling it a grilled cheese so that someone like me can say ‘I had a $44 grilled cheese last night.’”

My fiancée says, “You’re probably right, but that wasn’t what I asked—did you contact the wedding caterer?”

“Sorry, sorry. You’re right. I bet the bread is housemade, too.”

Taking On the $44 Grilled Cheese at Pamplemousse Grille

The dining room at Pamplemousse

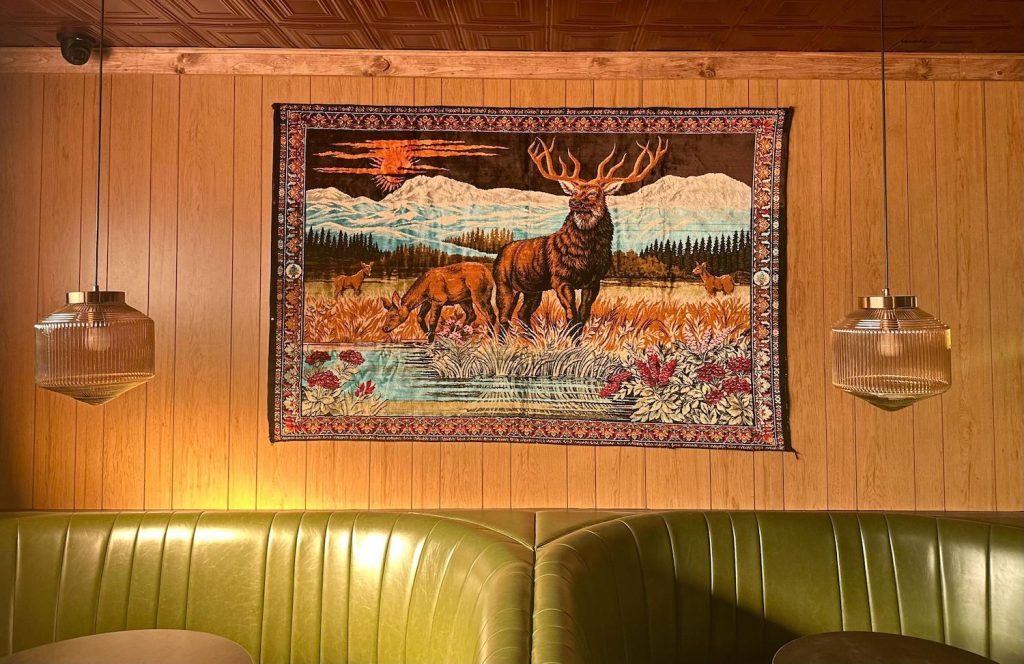

The second night we pull into the business park across from the Del Mar Fairgrounds—the fine, freshly waxed European automobiles parked below the somber gray workitecture—I’m ready, if still confused. Pamplemousse baffles me almost as much as that signed Banksy of a sandwich. In 2019, diners are addicted to the cult-of-new, going from one restaurant opening to the next as if they’re itching for their next fix. The tragic result is that the average lifespan of a restaurant is now between six and seven Yelp reviews. And yet Pamplemousse has thrived in this unsexy white-collar parking lot for 23 years. It doesn’t have an Instagram-ready wall (unless you count the rather awesome painting of a bearded man wearing a jean-jacket vest with no shirt, his fleshy belly proudly emancipated). It’s rarely included in any media outlet’s top lists, and the last notable clip I could find was a Naomi Wise review in the Reader in 2010 (this magazine’s David Nelson reviewed it in 1997). It plays by older rules, and it plays them well.

Pamplemousse was the biggest restaurant opening in San Diego in 1996. On the debut menu, there were house-baked miniature jalapeño muffins (still served to start every meal, slightly sweet and very good, their shy spice level set somewhere between Anglo and Saxon). Chef-owner Jeffrey Strauss claims to have invented truffle fries (still on menu); he once offered in the Union-Tribune to give his restaurant to anyone who could prove him wrong. Our server one night—clad all in black, he possesses a knowledge of the menu that’s almost marital in its intimacy—has been here since opening night as well.

Strauss made a name for himself in New York, where he grew up digging for clams on Fire Island. He went to Europe to study under Albert Roux at London’s La Gavroche (the first UK restaurant to earn three Michelin stars) and French nouvelle cuisine master Roger Vergé. Once in San Diego, you get the feeling he opened Pamplemousse as a showroom for a bigger idea—the one that earned him a sports car with the vanity license plate “TRUF FRY.”

Taking On the $44 Grilled Cheese at Pamplemousse Grille

Medley of Five Starters

The business idea most likely came to him between the years 1985 and 1993, when he served as executive chef of Glorious Food—the highest of high-end caterers in NYC, the sort you’d call if you were Jackie O and needed a dinner experience worthy of your cheekbones.

Strauss became the Glorious Food of San Diego. He is widely regarded as the go-to chef for high-end charity events, serving succulent osso bucco (still on menu) and lamb stew (still on menu) at major galas and fundraisers. He’s cooked for seven US presidents. There’s a social compact in goodwill cooking for world-beaters. If you’re the CEO of a bank and you’ve got a party to throw, you pay top dollar to that good-hearted chef from the gala who cooked the porcini-dusted John Dory with port wine sauce (still on menu). Strauss gave and gave and gave, earning a loyal following among the city’s elite.

At this point, Pamplemousse Grille seems less a restaurant and more a clubhouse for those friends. When I call, using a fake name, the host seems genuinely shocked she doesn’t have me in her system (or is calling my bluff, since they have caller ID). Point is, this feels like a hangout for regulars who don’t blink at a sandwich with a mortgage. The night we’re there, Salk Institute is hosting a 40-person dinner in the private dining room, and I’m betting it’s not their first. There is a seasoned gentleman at the bar in a formal, pressed boat-captain’s uniform, as if he finds himself on yachts at various points in the day and likes to be dressed for the occasion.

Taking On the $44 Grilled Cheese at Pamplemousse Grille

The restaurant’s exterior

It’s clear from the soft, farmhousey oil paintings of pigs (truffle hunters) and geese (foie gras) what kind of food to expect at Pamplemousse. A pamphlet for a special four-course truffle dinner is tucked into our thick steel menu. With carpet, cushioned wooden chairs, curtains, tablecloths, and acoustic paneling all over the ceiling—it is the quietest restaurant in the world. Hard as we try, we can barely make out what the couple immediately next to us is talking about. You could safely do some very loud insider trading here. The air itself feels soundproofed. In a modern restaurant world of hard, ear-splitting materials—concrete floors, steel chairs, roll-up garage doors—a soft, hushed room to eat and talk in feels less like an aesthetic than an antidote to the national noise disease. It’s not just nice, it’s salvational.

“We’ll start with the grilled cheese,” I say to the server. A lightning bolt of panic tears through me. I force myself to remember the magazine is paying for this meal, and my panic is replaced with guilt.

“Ah, the grilled cheese,” the server replies in the but-of-course way one speaks of icons.

Taking On the $44 Grilled Cheese at Pamplemousse Grille

Mixed Grille

Minutes later, he rests all $44 of the sandwich on the table with the blissful nonchalance of a pre-crash American economy. It’s smaller than I expected, with thin, soft white bread, jaundiced with butter and indulgence. I peel back the top slice and am disappointed to not see a full lobster tail in there, but instead small shreds of it engulfed in truffle cheese. I bite into it, trying to temper my expectations (spiritual enlightenment is among them, but only half-heartedly so). And what I taste is… a damn good sandwich, the crunchy edges of the toast giving way to the cakelike middle, the truffle’s primal food cologne, the lobster’s meaty sweetness. Top it with one of the pristinely ripe, blood-red heirloom tomato slices also on the plate, drizzled with balsamic reduction, and for a brief moment the serrated edges of life feel like silk.

Is it worth $44? If you have to ask this—and I most definitely do—Pamplemousse probably isn’t designed for you. With all due respect to Strauss’s skills, which are formidable, this is the most obscenely priced restaurant I’ve seen in years. We order a cup of white asparagus soup, split to share, and we’re presented two small teacups for $17. It’s a nice soup, creamy and with a distinct, clear flavor of those famous fine-dining albino shoots. But, as my fiancée observes, “At that price the soup should make your ears bleed with pleasure.”

Taking On the $44 Grilled Cheese at Pamplemousse Grille

The pastry station where the staff makes desserts and fresh donuts, rolls, and biscuits

I briefly entertain a conspiracy theory. Maybe Pamplemousse is priced to intentionally exclude. Instead of making it a private club for affluent members (which would be wrought with sticky social implications), just build an invisible wall made of menu prices. It’s a baseless theory (and they participated in Restaurant Week, which is a citywide discount promotion), but it still rattles as I write this.

The food at Pample is fine, good. There are hits, there are misses. This is not a place of modern cuisine. The printed menu is full of gold standards from yesteryear that have secured tenure. The kitchen does, however, create a long list of specials each night. It’s from those that we find our best dishes, like the Korean beef—lightly wet with a bulgogi-esque marinade, over gingery rice and julienned root vegetables. Or the halibut, seared to a George Hamilton tan yet still tender inside, over spaetzle with chanterelle mushrooms and fat-supplying bits of duck confit. We order the mixed grille of game meats—venison, quail, and duck—and the venison is tender in a spot-on au poivre (pepper sauce), but the tiny quail has done what quail has done for thousands of chefs—dry out—and the fat on the duck is unrendered, almost unchewable.

Taking On the $44 Grilled Cheese at Pamplemousse Grille

The chocolate-caramel cake with housemade marshmallow

For dessert, definitely try the warm chocolate-caramel cake with toasted, housemade marshmallow, graham cracker crumbs, and chocolate gelato. It’s the quintessential ’80s restaurant dessert—a molten chocolate cake—except caramel oozes from the center, and that marshmallow makes a standard s’more taste like used chewing gum by comparison.

I’m not one to decide how much a chef can ask in return for their talent and toil. They’ve worked their duff off to earn their reputation, and set their prices accordingly. All I can say with absolute confidence is that I had a $44 grilled cheese sandwich last night.

Taking On the $44 Grilled Cheese at Pamplemousse Grille

Grilled cheese