Coronado, connected to San Diego by that famous blue comma of a bridge, possesses a prim by-golly-ness unseen in the US since the 1950s. Sidewalks look dry cleaned and pressed. Lawns are obsessively edged like the beds in a naval barracks (military families are the local lifeblood). Police are enthusiastically proactive about maintaining the city’s pervasive nuzzle of civility. A boat captain recently told me Coronado holds some sort of national record for speeding tickets issued, tossing them like confetti to welcome brazen, lead-footed interlopers unaware that this is a place of serenity. The official city emblem could appropriately be a V-neck sweater or a radar gun.

If this sounds disparaging, I assure you it’s not. In a chaotic modern world, there’s something reassuring about a city that practices self-care. When guiding out-of-town guests through the region’s greatest hits, I enjoy Coronado. I simply check my debatable urban habits at the bridge.

Serẽa’s Sustainable Seafood Menu Is Admirable, but Lacks Side Dishes

Clockwise from top: Grilled lamb chops; Baja striped sea bass sashimi; grilled octopus; Baja red snapper. Center: The Lagoon cocktail with tequila, watermelon, and coconut liqueur

As a historical structure, the Hotel Del sits somewhere between Hearst Castle and the Betsy Ross House, both formidable and humbly made of wood, painted virginal white like grandma’s shutters. From the apex of the bridge, you see its maroon spires rising like giant tubes of lipstick. Erected in 1888 by architect James W. Reid, it’s less a hotel at this point than a time capsule stuffed with the collected special memories of San Diegans and travelers across the globe.

Serẽa’s Sustainable Seafood Menu Is Admirable, but Lacks Side Dishes

Fresh seafood is delivered daily, then laid out on ice in the dining room

It’s on the National Register of Historic Places, which means getting approval to change one shingle is about as fun as a self-inflicted compound fracture. And yet current owner Blackstone Group got permission for a $200 million renovation, which includes a new grand entrance, a palm-lined walkway, underground parking, new rooms, a new pool, a new roof—and a new fine-dining restaurant in Serẽa.

Serẽa’s Sustainable Seafood Menu Is Admirable, but Lacks Side Dishes

Diners can select a whole fish, such as Huachinango, red snapper caught in Baja

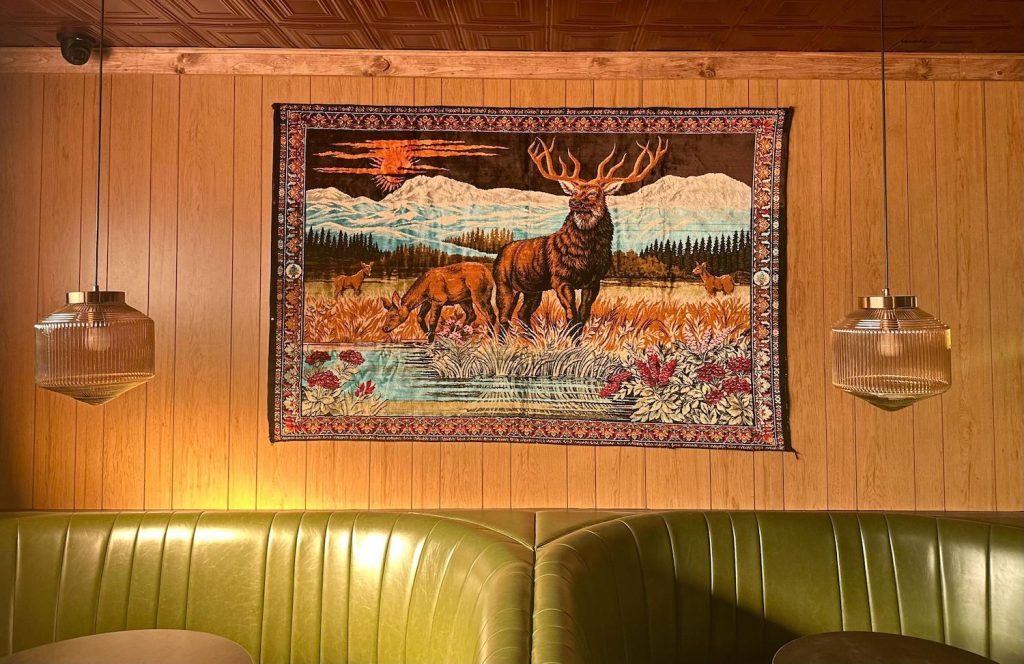

This particular room has been a variety of entertaining things, the most nostalgically unsettling of which was a ladies-only restaurant with a bowling alley (the gender segregation is the unsettling part, though bowling culture has been known to turn a stomach or two). It was the Prince of Wales Grille through America’s disco and cocaine decades (the prince dined here and said nice things), and then 1500 Ocean for 13 years. For Serẽa, they brought in Vegas-based Clique Hospitality (MGM Resorts, Mirage, Cosmopolitan in Vegas; Pendry San Diego). Clique is the new generation of Vegas, coveting modern architecture and quality design over fake Eiffel Towers and explosive neon. Clique did what had needed to be done to this space for generations—opened it up, poured the space into the patio and that billion-dollar ocean and sun. It’s lighter and brighter, the restaurant equivalent of Mediterranean resort wear.

Serẽa’s Sustainable Seafood Menu Is Admirable, but Lacks Side Dishes

Left: The red snapper is grilled over an open flame or flash fried; Right: Watch as the fish is deboned and prepared tableside.

Only thing that hasn’t changed is the waitstaff. There’s the man I’ve seen here for years, with a white shock of hair and a face so tan it seems to go on vacation by itself, leaving the rest of his body at home. The staff communicates like old card buddies. They’re not the fastest (one night we wait an hour between appetizers and entrées), but at this point they’re as loved and historical as the grand ballroom itself. Certain things you should hesitate before replacing, and humans are one of them.

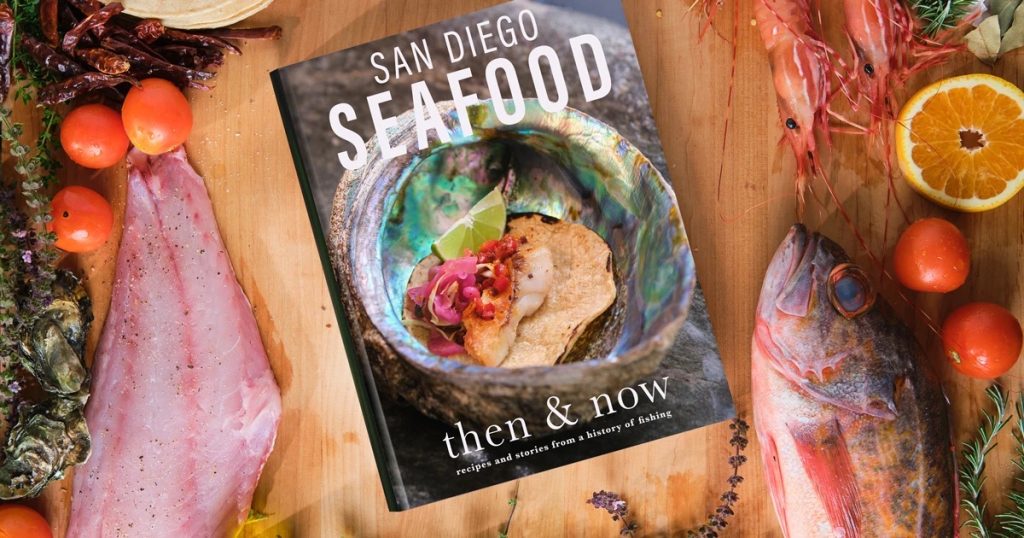

Serẽa’s executive chef is JoJo Ruiz, who also handles Lionfish at Pendry. Ruiz saw his life’s purpose in the sustainable seafood down at Tuna Harbor Dockside Market, and has won James Beard Awards for championing responsible oceanic eating. The big idea at Serẽa is just that.

Serẽa’s Sustainable Seafood Menu Is Admirable, but Lacks Side Dishes

Octopus at Sere~a is grilled over charcoal and seasoned with sumac and red chimichurri

Local fishermen deliver rockfish and spot prawns caught each morning. Striped bass and snapper are refrigerated and driven from Baja. They’re laid out like treasures on ice in the dining room. You select your whole fish (you could watch out for cloudy eyes, which means it’s old, but Ruiz would never allow that), it’s taken into the kitchen, cooked whole, and presented tableside, where the server dishes out fillet meat. When finally on the plate, it’s bone simple: a mound of steaming meat from our Huachinango red snapper has only a slick, supple tincture of olive oil, lemon, and salt. What you taste is what fishing families tasted for generations before the invention of nationwide frozen seafood distribution—sweet meat, clean as deep-ocean air, startlingly juicy, tender as a human cheek. Since about 65 percent of seafood consumed in the US is frozen and imported, most of the country hasn’t tasted this in decades.

Serẽa’s Sustainable Seafood Menu Is Admirable, but Lacks Side Dishes

Greek salad with feta

A three-pound snapper costs $85 to feed two of us, and no side dishes are included with the order. This stings. But fresh, local seafood isn’t cheap, and neither is the furniture at Serẽa. Only the clueless come here to hunt bargains. Including a grain or vegetable would be a kinder gesture, though.

Serẽa’s Mediterranean fixation shows up first in the saganaki, one of Greece’s many fine gifts to humanity, with griddled kefalotyri cheese, blistered Peppadew peppers that burst their sweet acidic garden juice on bite, lemon, herbs, and baugna càuda (olive oil with its umami spiked by anchovies and garlic). You could quibble that the saganaki should be more deeply browned, and ours isn’t really melted. It eats more like slightly warmed cheese than traditional saganaki, but it’s awesome. Nab that charcoal-grilled octopus, crispy-tender tentacles brought alive by sumac’s lemony impersonation and a deeply electric red chimichurri. Their Greek salad is cut so large I almost expect to find a whole tomato under the huge wedges of herb-flecked feta. It’s as delicious as it is a task to eat.

Serẽa’s Sustainable Seafood Menu Is Admirable, but Lacks Side Dishes

Grilled lamb chops with cripsy marble potatoes and sunchokes

Their “sashimi” is cut so thin it’s more like a crudo, with gossamer Hawaiian bigeye tuna preciously dotted with caper relish, shisho, pickled fennel, and a 20-year-aged balsamic, topped with whole tumbleweeds of crispy onions. That’s a lot of sharp flavors, but they work in concert to replace the boring ol’ lemon or lime. The hiramasa gets an almost creamy aguachile with cashews. Cashews are the dairy cow of tree nuts, all creamy fat. But that beautiful fish deserves less of a smothering.

Serẽa’s Sustainable Seafood Menu Is Admirable, but Lacks Side Dishes

The view from the dining room

From the entrées, both the swordfish and the lamb will go well with the ring in your pocket. The swordfish is “en papillote” (steamed in a gift wrap of parchment paper). Swordfish got a bad rap for years, because glorified sports bars tried to get fancy and served the steaks so tough and dry your saliva glands would give up and tell your brain to swallow it whole. In paper, the meat sits in a juicy sauna of its own steaky goodness and comes out luscious. The lamb isn’t for traditionalists, served with a pomegranate-molasses rub and a sweet chermoula (a sauce of garlic, cumin, coriander, and sometimes cloves, cinnamon, or even raisins). The sweet dances nicely with the char from the grill.

None of the sides floated our boat. The mushrooms were just kind of sautéed under a sunny hen’s egg, not transformed in a way that justified the $12. And they really shouldn’t call that vegetarian option a “paella,” because it tastes more like a pretty dry dirty rice.

Serẽa’s Sustainable Seafood Menu Is Admirable, but Lacks Side Dishes

Banana chocolate bar dessert

Don’t skip the banana chocolate bar dessert. What a log of good sin. It’s got chocolate halva (a dense, nutty confection), bananas torched and brûléed, banana-dulce ice cream, and a salted caramel sauce.

Serẽa’s a much better incarnation than 1500 Ocean, which felt hidden as if afraid of getting wrinkles. This is a restaurant that fully understands why people come to The Del. They come for that white noise ocean lullaby, extending so far west in front of your eyes its destination just might be the afterlife.

Serẽa’s Sustainable Seafood Menu Is Admirable, but Lacks Side Dishes

Justin McChesney-Wachs