Our Genetic Legacy Drone Community Group San Diego -4

Courtesy of Our Genetic Legacy

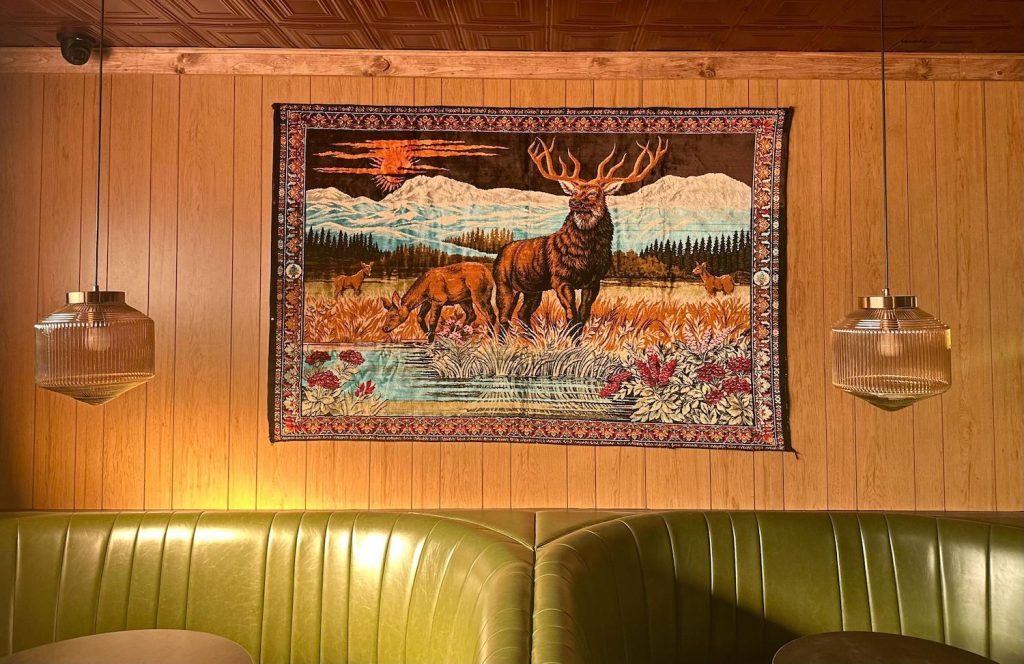

To most people, the town of Julian means apple pies and dusty antique stores. But beyond the town’s all-American reputation lies a hidden history, long buried and obscured. A group of young, determined women are working to uncover Julian’s long-forgotten history with the help of new state-of-the-art technology through a local non-profit.

Julian was once a major center for Black settlers who came to Southern California in the late 1800s. But historical whitewashing means the legacy and contributions of Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) communities in Julian have been obscured or outright stricken from the history books.

But not for long.

Shellie Baxter, a long-time historian and genealogical researcher based in San Diego, is the founder of Our Genetic Legacy (OGL), a San Diego-based non-profit working to empower a new generation of BIPOC female innovators. Through OGL, Baxter is launching an ambitious new program seeking to document the history of Julian’s early Black pioneers by training young BIPOC women to fly drones outfitted with the latest scanning technology.

Shellie Baxter Our Genetic Legacy Skydiving San Diego Drone Community

Courtesy of Our Genetic Legacy

Baxter’s frustration with the erasure of BIPOC people in American history, along with her background in genealogical research inspired OGL’s creation in 2018. In 2022, OGL began to branch out from its genealogical research and started its DRONe (Descendants Recovering Our Names) Project. Through the DRONe Project, Baxter hopes to inspire a new generation of BIPOC female innovators in the field of digital historic preservation.“By providing the girls with training and resources while affirming who they are culturally, they will be more confident in white, male-dominated spaces which will increase diversity over time,” Baxter explained. “ All of our programs are about learning while doing.”

Using LiDAR (light detection and ranging) enhanced drone technology, the DRONe program seeks to recover and record underground legacies before the damaging effects of weather and time completely erase them from history. LiDAR can create an image of the earth’s surface that is invisible to the naked eye, such as disruptions in terrain and indicators of past land uses. The technology is commonly used to detect unmarked graves and help archeologists uncover hidden ruins.

View this post on Instagram

Following the Civil-War, San Diego County became home to numerous Black pioneers through both forced and voluntary migration during the Reconstruction Era. Baxter’s research led her to set the program’s sites on the Julian Cemetery and Harrison Serenity Ranch as the areas for the DRONe Program to map and survey.

Harrison Serenity Ranch is the site of the last home of formerly enslaved Black pioneer, Nathan Harrison—the first Black landowner in San Diego County. And like many other locations throughout the US, the Julian Cemetery contains the graves of BIPOC families whose legacies have been lost due to inaccurate census data and misclassification in historical records.

Many of the graves in the Julian Cemetery have little or no documentation to account for those buried due to the loss of the original burial records in a fire in 1957. Baxter selected the Julian Cemetery to map to restore the ethnic identities of Julian’s early inhabitants and see if the LiDAR data supports headstone placements in the cemetery, as well as other unmarked graves or those with markers such as stones or other non-identifying signifiers. Baxter’s hope is that with the use of LiDAR technology, participants will be able to ensure that all graves are properly marked, accounted for, or even be able to possibly detect unmarked graves.

Our Genetic Legacy Drone Community Group San Diego

Courtesy of Our Genetic Legacy

Baxter recruited a cohort of teens for the DRONe Program. Under the supervision of certified drone pilots, these “herstorians” are able to use the LIDAR technology while studying for their own drone pilot’s license exam.

The pictures and video collected by the cohort’s research will also be used to create exhibits for OGL’s virtual We The People Museum, a BIPOC history project set to go live in August 2023.

“The Herstorians are actively involved in the growth and development of the museum,” Baxter said. “Which gives them insight into the fundamentals of business operation whether or not they choose to go into business for themselves.”

The DRONe Project’s participants all come from a multitude of backgrounds. Aklesia Mekuria, a 16 year-old participant in the program, explained that even though she had prior experience with drones, she had no prior knowledge about the lost history of Julian Cemetery and Harrison Serenity Ranch.

Our Genetic Legacy Drone Community Group San Diego

Courtesy of Our Genetic Legacy

“I only went to Julian a couple of times, maybe twice before the program,” Mekuria said. “I didn’t know anything about Harrison-Serenity Ranch, or much about the history of Julian at all. I just knew about the apple pies and that was pretty much it.”

“I think programs like this for girls that come from BIPOC backgrounds gives them more confidence,” she added.

Through the DRONe Project and the We The People Museum, Baxter hopes that both the participants of the program and those who view the exhibits will come away with a new understanding of the importance of documenting San Diego’s forgotten history and the greater contributions that BIPOC communities have made to the US.

“I hope to normalize the inclusion of BIPOC in historical narratives and encourage people to openly question narratives that erase BIPOC,” Baxter said. “I hope that visitors of color will feel seen and valued. And I hope that non-BIPOC visitors will celebrate the accomplishments of BIPOC as human beings.”