The year was 2018, and Dr. Gabriel Wardi saw a potential solution to a long-running problem in healthcare: sepsis. Wardi, the medical director for hospital sepsis at UC San Diego Health, says sepsis—an overzealous immune system response to an infection—kills about 10 million people a year worldwide, including 350,000 people in the United States.

Part of the problem with sepsis is that there are a lot of ways it can present, which makes it tricky to diagnose. For years, Wardi had been trying to see if electronic health records could trigger an alert for doctors and nurses when someone becomes at risk.

“Unfortunately, those early alerts were wrong almost all the time, and you can imagine that in a busy hospital, your initial reaction is, ‘Get this thing away from me,’ because it’s wrong all the time, it changes your workflow, and no one likes it,” he says.

But when artificial intelligence entered the scene, Wardi wondered if AI models could more accurately predict who’s going to get sepsis.

“We focused on coming up with a way to pull data out of our emergency department in near real-time, look at about 150 variables, and generate an hourly prediction [for] who’s going to develop sepsis in the next four to six hours,” Wardi says, adding that the resulting deep-learning model is helping save some 50 lives a year at UC San Diego Health.

Across San Diego County, AI is reshaping healthcare. It transcribes audio from appointments and summarizes patient notes. It helps drug companies decode genetic data. It writes draft responses to patient questions. It chats with people with mild cognitive impairments. It even identifies breastfeeding-related conditions from pictures taken with a phone.

All of these enhancements are leading to lasting changes that will dramatically improve medicine, says Dr. Christopher Longhurst, chief medical officer at UC San Diego Health.

“I think the promise is a little overhyped in the next two or three years, but in the next seven to nine years, it’s going to completely change healthcare delivery,” Longhurst adds. “It’s going to be the biggest thing since antibiotics, because it’s going to lift every single doctor to be the best possible doctor and it’s going to empower patients in ways they never have been before.”

These may sound like high ideals, but the money piece of this equation seems to speak to a bright future for AI in healthcare. Investors are taking note of the technology’s promise. According to a recent Rock Health report, a third of the almost $6 billion invested in US digital health startups this year went to companies using AI.

However, all of these innovations come with big questions: Do patients know when AI is being used? Is patient data protected? Will human jobs be replaced? Does anyone really want to talk to a robot about their health? Some worry the technology is progressing so quickly that these concerns will go unaddressed.

“I just hope we don’t get too excited before the technology is really where it needs to be,” says Jillian Tullis, the director of biomedical ethics at University of San Diego. “I’m thinking of Jurassic Park—just because we can do it doesn’t mean we should do it.”

The promise—and pitfalls—of AI as a diagnostic tool

Even providers themselves aren’t always keen on utilizing AI programs such as Wardi’s sepsis model.

“Doctors and nurses are usually very, very smart people, and not all of them are going to be excited about having some kind of form of artificial intelligence suggest that someone might be developing sepsis,” Wardi says. “The more senior the physician, the more likely they are not to find value in the model. It could be a generational thing … Younger people are more excited about AI.”

Wardi compares the skepticism around AI to 19th-century physicians’ resistance to the stethoscope. “[Doctors thought] it had no value and would ruin the profession,” he says. “Now, it’s a symbol of medicine.”

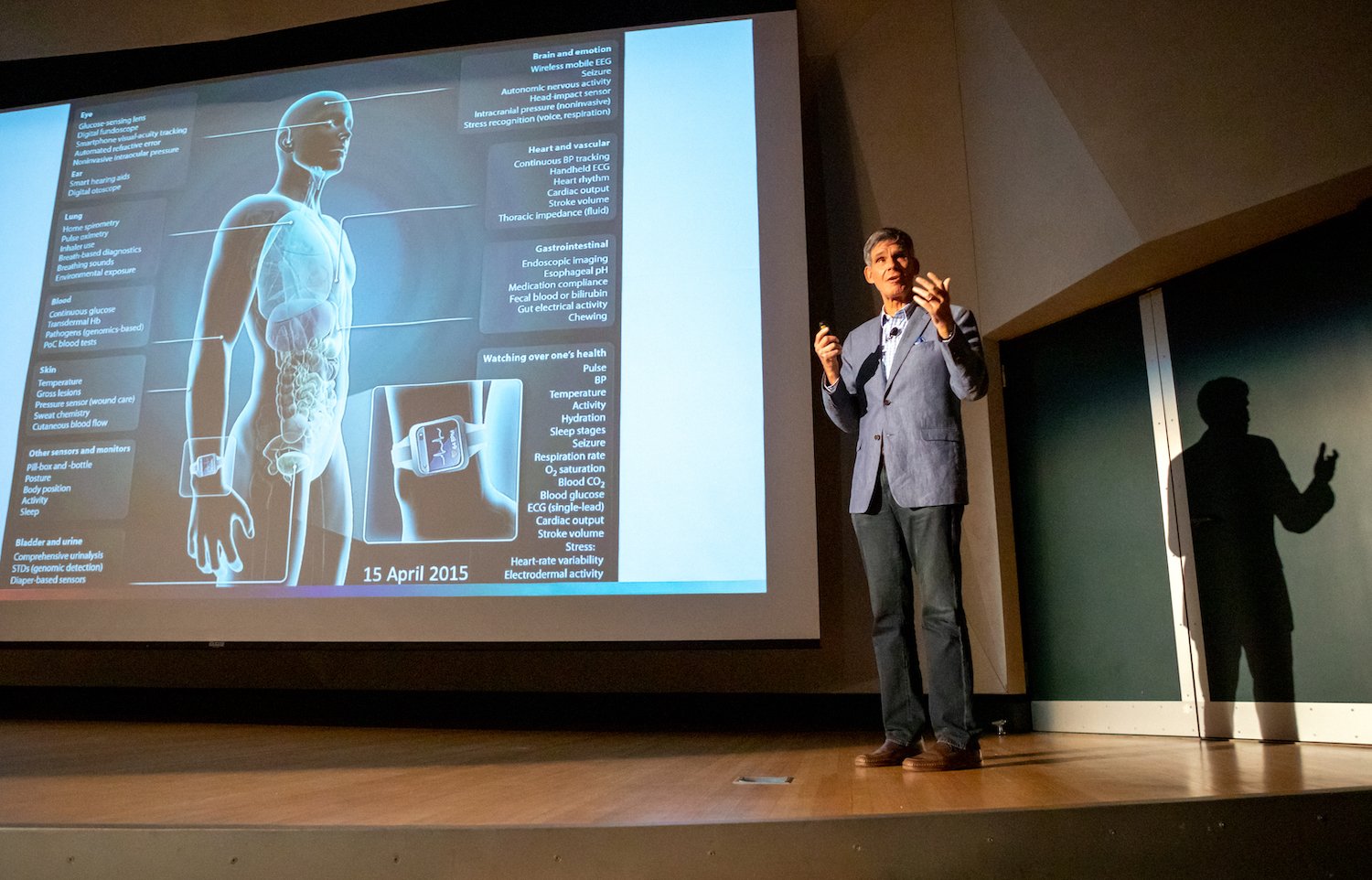

Methods like the sepsis model can be expanded to predict the risk of other diseases, such as cardiovascular conditions, Alzheimer’s, and cancer, says Dr. Eric Topol, director and founder of the Scripps Research Translational Institute.

“So we take all of a person’s data—that includes their electronic health record, their lab tests, their scans, their genome, their gut microbiome, [and their] sensor data, environmental data, and social determinant data,” he explains. “We can fold that all together and be able to very precisely say this person is at high risk for this particular condition.”

According to Topol, Scripps researchers are even using pictures of the retina to predict Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s years before any symptoms show up. “Machine eyes or digital eyes can see things that humans will never see,” Topol adds.

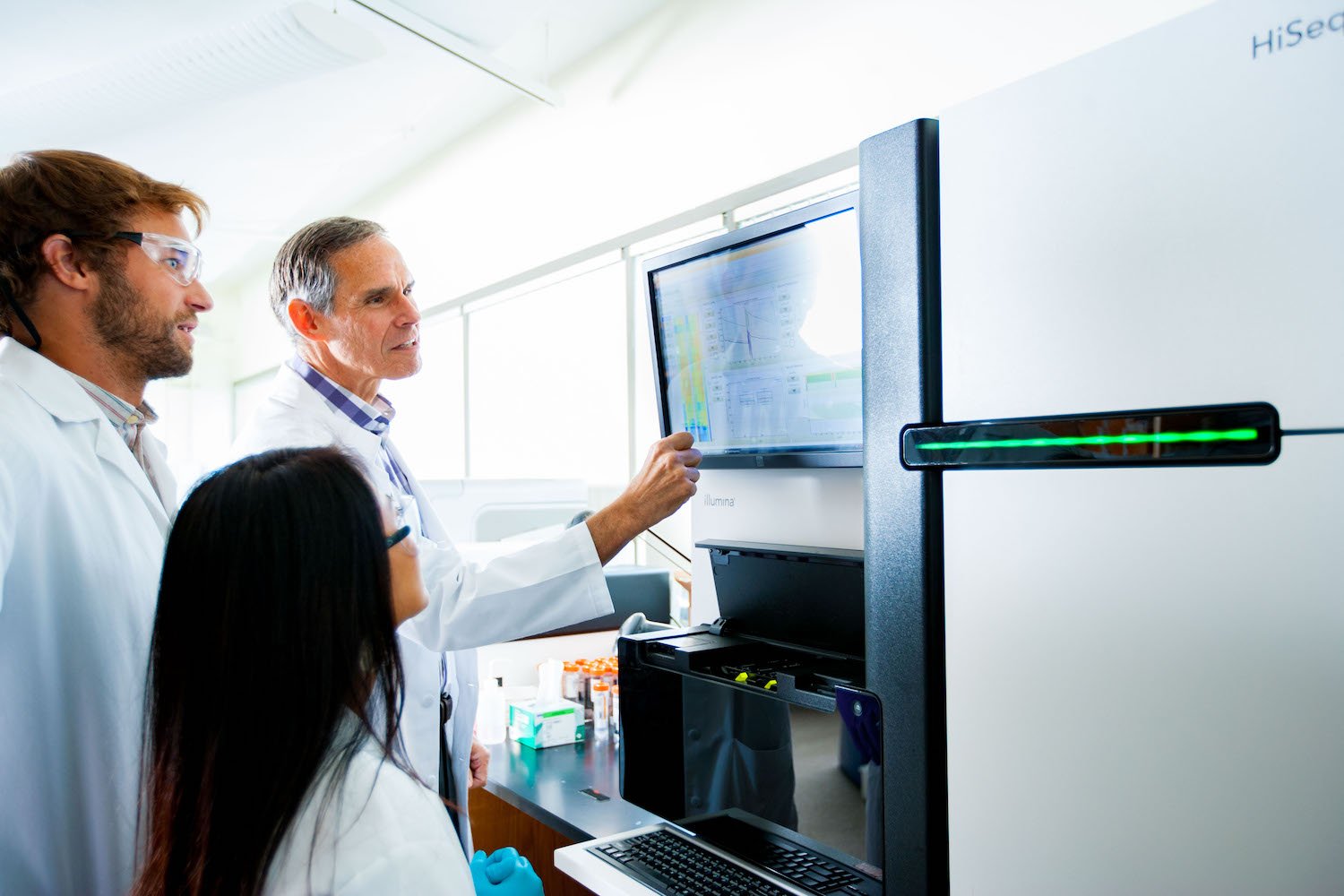

Meanwhile, at the San Diego biotech company Illumina, researchers are using an algorithm to analyze genetic information and find mutations that cause disease.

But creating this type of intelligence is a challenge compared to building programs like ChatGPT, which train on data from the internet. Dr. Kyle Farh, VP of Illumina’s Artificial Intelligence Lab, has turned to primates, sequencing their DNA and using that data to train the company’s model, PrimateAI-3D. He hopes to one day use the model to diagnose rare genetic diseases.

Tullis at USD says she’s all for predicting and preventing illness, but she’s worried about the other uses of AI.

“When I read stories about doctors who are fighting with insurance companies about whether or not patients should get certain procedures or treatment, but the insurance company uses an algorithm to make a determination… I get really nervous,” she says.

Diagnosis often requires a human touch, she adds.

“You can look at people’s nail beds; you can look at lumps or rashes in particular ways; you can feel people’s skin if it’s clammy and cold,” she says. “The algorithm can’t do that.”

Saving time while protecting patient data

Anyone who’s used an AI model to draft an email or write a cover letter knows it can save a massive amount of time. And doctors and nurses in San Diego are already utilizing AI to take care of some of their more menial tasks.

Several health systems, including Scripps Health, use AI to generate post-exam notes, answer patient questions, and summarize clinical appointments. It can reduce documentation time to “about seven to 10 seconds,” says Shane Thielman, chief information officer at Scripps. “It’s enabled certain physicians to be able to see additional patients in the course of a given shift or day.”

UCSD uses a similar system. According to Longhurst, it’s freed doctors up to focus on patients—not computer screens—during appointments.

“That’s really about rehumanizing the exam room experience,” he says. Since they don’t have to take notes, physicians can make eye contact with patients while the tech transcribes their conversations.

But the approach raises concerns about consent and data privacy. Jeeyun (Sophia) Baik, an assistant professor who researches communication technology at University of San Diego, recently studied loopholes in federal HIPAA law that health data can fall into.

HIPAA does not currently protect health data collected by things like fitness apps or Apple Watches, she says. And that legislative gap “could apply to any emerging use cases of AI in the areas of medicine and healthcare, as well,” Baik adds.

For example, if physicians want to utilize protected health data for any purpose beyond providing healthcare services directly to the patient, they’re supposed to get the patient’s authorization. But it’s debatable whether that applies if healthcare providers start to use the information to train artificial intelligence.

“It can be controversial, in some cases, whether the use of AI aligns with the original purpose of healthcare service provisions the patients initially agreed to,” Baik says. “So there are definitely some gray areas that would merit further clarification and regulations or guidelines from the government.”

A recent California state bill, SB 1120, attempts to clear up those gray areas by requiring health insurers that use artificial intelligence to ensure the tool meets specified safety and equity criteria.

Thielman with Scripps Health says patients must always give consent before the AI tool takes notes on appointments. If a patient declines, providers won’t use the technology. However, “it happens very rarely that we have a patient that doesn’t consent,” he adds.

And, he continues, a human always looks over automated, AI-generated messages answering patient questions. But Scripps doesn’t tell patients that it’s using AI “because we have an appropriate member of the care team doing a formal review and signing off before they release the note,” he says.

It’s the same case at UCSD.

“There’s no button that says, ‘Just send [the message to the patient] now,’” Longhurst explains. “You have to edit the draft if you’re going to use the AI-generated draft. That’s adhering to our principle of accountability.”

Jon McManus, chief data, AI and development officer for Sharp HealthCare, says he realized an internal AI model was necessary to ensure employees and providers didn’t accidentally input patient data into less secure algorithms like ChatGPT. “We were able to block most commercial AI websites from the Sharp Network,” he explains. Instead, his team created a program called SharpAI. It’s used for tasks like summarizing meeting minutes, creating training curriculum, and drafting proposed nutrition plans.

Fixing mistakes—and possibly making them

With artificial intelligence technology, telehealth services could get way more advanced—Jessica de Souza, a graduate student in electrical and computer engineering at UCSD, is currently working on a system that would allow parents experiencing breastfeeding problems to send photos of their breasts to lactation consultants, who could use AI to diagnose what’s wrong. De Souza created a dataset of breast diseases and trained AI to identify patterns that could indicate issues such as nipple trauma.

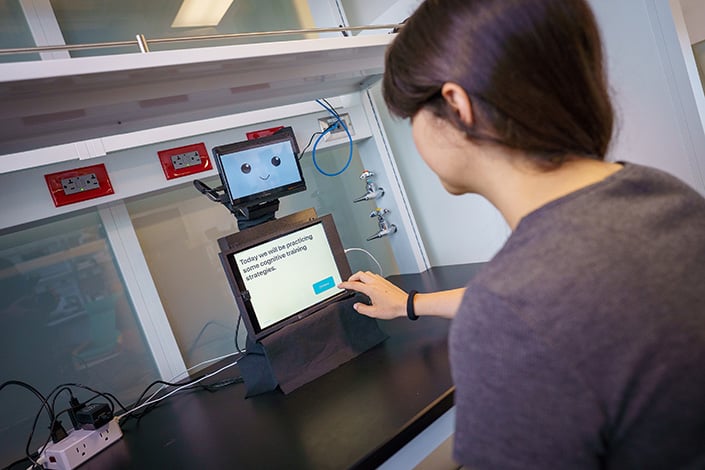

Meanwhile, Laurel Riek, a computer science professor at UCSD, designed a small, tabletop robot called “Cognitively Assistive Robot for Motivation and Neurorehabilitation,” or CARMEN (the name is inspired by Carmen San Diego). CARMEN helps people with mild cognitive impairment improve memory and attention and learn skills to better function at home.

“Many [patients] were not able to access care,” she says. “The idea behind CARMEN is that it could help transfer practices from the clinic into the home.”

Uses like these offer another vision for AI in healthcare: to improve patient care by helping doctors assess conditions and find mistakes.

“One of the big things is getting rid of medical errors, which are prevalent,” Topol says. “Each year in the United States, there are 12 million diagnostic medical errors.” According to Topol, those errors cause serious, disabling conditions or death for about 800,000 Americans per year.

He believes that AI can help shrink that number considerably. For example, doctors are utilizing it to review cardiograms, checking if there’s anything a human review missed.

But, Topol cautions, you can’t rely solely on AI. “In anything involving a patient, you don’t want to have the AI promote errors,” he says. “That’s the thing we’re trying to get rid of. So that’s why a human in [the] loop is so important. You don’t let the AI do things on its own. You just integrate that with the oversight of a nurse, doctor, [or] clinician.”

No matter how advanced artificial intelligence programs get, he sees no future where AI would handle diagnosis without human eyes.

“You don’t want to flub that up,” he says. “And patients should demand it.”

Algorithmic bias

An additional hope for AI is that it could correct for implicit racism in medicine, since machines, in theory, don’t see skin color. But the data on which algorithms are built is inherently imperfect.

“The medical bias could be already built into the existing information that’s out there,” Tullis says. “And, if you’re drawing from that information, then the bias is still there. I think that’s a work in progress.”

For example, an AI tool designed to detect breast cancer risk would be trained on previously gathered population data. “But they didn’t get as many Black women as they would like to be included in that data,” Tullis explains. “And then what does that mean for the quality of the data that has been used to maybe make decisions?”

But there’s bias in every data set, Longhurst says. The key is to choose the right data for the population you’re working with to help address disparities. He points back to the sepsis model. That algorithm, he says, actually performed far better in UCSD’s Hillcrest hospital than in La Jolla.

“Why is that? Well, we tuned the algorithm to identify cases of sepsis that weren’t being picked up [by physicians] until later,” he adds. “We serve different populations in those different emergency departments.”

Patients at the Hillcrest location tend to be younger, which makes it harder to diagnose sepsis early, he says. But the AI algorithm helped to close that gap.

“These tools are going to change healthcare delivery more in the next 10 years than healthcare has changed in the last 50,” Longhurst says. But he hopes the industry doesn’t get ahead of itself—after all, he suggests, what if the FDA approved a new drug for breast cancer and simply said, “It has very few side effects?”

“You’re like, ‘Well, that’s great, but how does it work?’ They’re like, ‘Well, we don’t really know. We don’t have the data,’” he continues. “That’s what’s going on now. It’s like the Wild West. Our argument is that we really need local testing that is focused on real outcomes that matter to patients. That’s it.”