Santa Margarita River California Trout Conservation San Diego

Illustration by Samantha Lacy

The low, concrete Sandia Creek Bridge over the Santa Margarita River isn’t exactly guilty of murder. But it has the same effect on endangered Southern California steelhead living downstream as a mobster garroting a disloyal colleague with piano wire.

That’s why people such as Mary Larson have spent the last 22 years buried in newspapers and microfiche archives, compiling evidence, like cold case detectives, to prove steelhead once flourished in places like the Santa Margarita. Confirm that, and the government will put money on the table to restore the river.

With the help of Larson and others like her, CalTrout—a conservation nonprofit dedicated to protecting California’s watersheds—secured $18 million to erect a new, 20-foot-high steel bridge that clears a path for steelhead. Goodbye, low fish-blocking bridge. Hello, free-flowing Santa Margarita.

Santa Margarita River Dam California Trout Conservation San Diego

Illustration by Samantha Lacy

Once Sandia Creek Bridge is eliminated, the Santa Margarita will become the first Southern California river freed of any human-made barrier from its headwaters to the Pacific Ocean. And steelhead will no longer be choked off from an extra 12 miles of pristine breeding grounds.

Larson first started working for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife in 1988. In 2001, she moved into steelhead restoration work. For her, that might mean scouring hand-scrawled records from the first missions that colonized California, searching for the word “trucha” (the Spanish word for trout), or cataloging an old fishing scrapbook full of Andy Griffith–like men proudly bearing their steelhead catch near a creek she studied along the Malibu Coast.“It’s a lot of work just trying to figure out where the fish were,” Larson says. “Some streams … were people’s secret fishing holes that they didn’t tell anyone about.”

From a distance, the bend in the Santa Margarita which the new bridge will soon span lives quietly in a canyon bed protected by a privately managed preserve. On the winding drive there from Fallbrook, squatty coastal sage scrub fades into tall leaning oaks trellising the road, casting magical, dappled light across the water.

Santa Margarita River California Trout Conservation San Diego Illustration

Illustration by Samantha Lacy

Nobody has reported seeing a steelhead here in recent memory. The fish’s federally endangered designation carries such weight that casting a pole is prohibited in the whole Santa Margarita and any other rivers that might be home to a steelhead. But these special fish were recently detected another way.

A geneticist by training, Sandy Jacobson tells me that new scientific technology sniffed out steelhead below Sandia Creek Bridge. Digital methods can pinpoint and amplify a small amount of steelhead DNA from a single water sample. It’s one thing to find scrapbooks hinting steelhead thrived in these waters decades ago; quite another to locate their genetic material floating somewhere below the bridge.

Jacobson directs the work of CalTrout in California’s South Coast and Sierra regions. She began her career in cancer research but is also a fly fisherwoman who wrote a grant to do genetic surveys for fish trapped behind barriers.“I wanted to know where the native trout were,” she says.

As I reported this story, it finally dawned on me that steelhead and trout were being used interchangeably by my sources. Growing up, I thought trout belonged to my native Wisconsin. On the contrary, its progenitors are steelhead, these native Pacific Ocean residents who fight river currents to mate in the cool headwaters of Western rivers.“These fish all began as ocean-dwellers, just as life itself is derived from the ocean,” says Mark Capelli, the South-Central California steelhead recovery coordinator for the National Marine Fisheries Service. “They evolved with the landscape of Southern California and use every part of the watershed, from the estuary— or the river’s mouth—to the farthest upstream tributaries.”

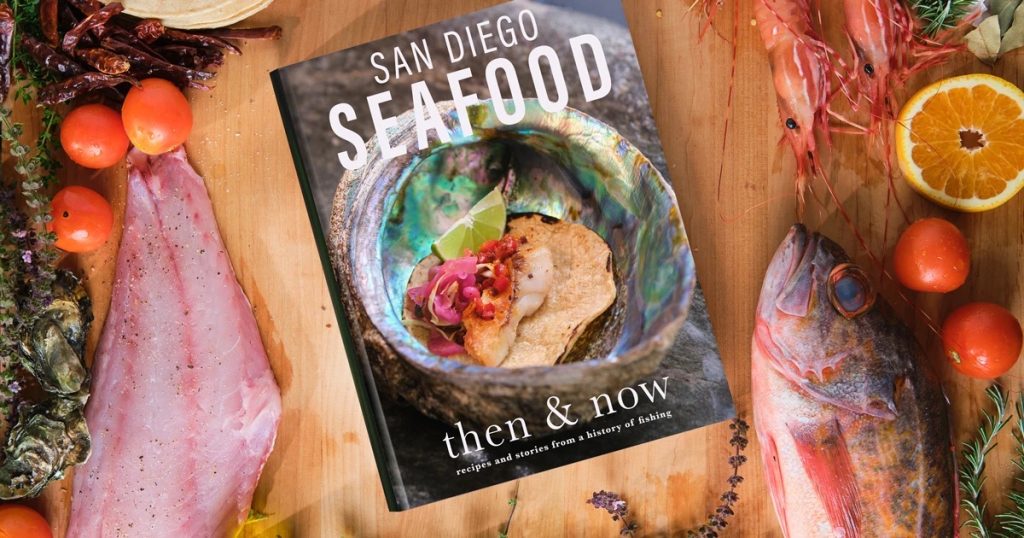

For Southern California steelhead conservationists, old fishing scrapbooks are more than mere memories—they’re evidence that the now-elusive fish once thrived in the Southern California rivers. A family shared these photos with the CA Dept. of Fish and Wildlife.

That’s the way it was until California’s settlers lined rivers with concrete and dammed them for drinking water. River habitat has been so destroyed that, though rainbow trout and Southern California steelhead are biologically the same fish, the latter has been on the federal list of endangered species since 1997.

And that’s also why, any time I wanted, I could glide my fingers over the embalmed scales of a 34-inch rainbow trout—the inland sister to the steelhead—nailed to my father’s wall. Not because they’re native to the Midwest, but because they adapted to thrive all over the world.

Steelhead were introduced on every continent except Antarctica, Capelli tells me. But they are truly native to Southern California.“They are part of the SoCal story,” he adds.But steelhead are an introverted fish—you might call them loners. Scientists don’t know much about what adult steelhead do when they return to the ocean after mating in terrestrial waters. They don’t school up and travel by the hundreds like Pacific salmon. No one is out trolling or casting off a pier, hoping for a strike from the salmon family’s sleek, elusive cousin whose skin looks touched by a rust-red watercolor brush stroke.

Santa Margarita River California Trout Conservation San Diego Department of Wildlife Fly Fishing Photos

Steelhead are a keystone species, an animal whose well-being determines the health of its ecosystem. They’re also tough. They can withstand low-oxygen environments and huge temperature swings and have even been found surviving in pools of water reaching 86 degrees Fahrenheit. Southern California steelheads’ endangered existence means the watersheds where they are born, mature, leave, and return to are also in peril from development and human-caused climate change.“

A lot of very experienced fish biologists who don’t have much familiarity with Southern California are amazed the fish exists at all,” Capelli says.

Removing dams, low bridges, and barriers is essential for the survival of steelhead. And water quality in the Santa Margarita River is key not only for the health of its creatures, but humans, too. The growing city of Fallbrook, home to more than 32,000 residents, will soon be drinking from the Santa Margarita River as drought-parched Southern California towns search for more local water supplies. If steelhead are there, that means the water is healthier for humans. Getting rid of the low concrete bridge is a win for fish and people.

On a brisk January morning, Larson stood a stone’s throw from the offending Sandia Creek Bridge, ready to bear witness to the fruits of her long labor. Construction workers, contractors, archaeologists, biologists, tribal representatives, and environmental activists stood in a large circle, gathered to plot the bridge’s demise.

View this post on Instagram

The group trekked single-file to a meadow off De Luz Road where materials would be stored during construction. Bridge builders in fluorescent-orange-and-white hard hats watched uneasily as a biologist staked out patches of rare flowering plants with short, pink flags—indicating areas that should be preserved in the middle of their new work zone. The scene was emblematic of the historic conflict between development and wildlands in California.“Everything is sensitive habitat now. It’s been that way for a long time,” says Bill Saumier, the cool-natured construction manager at Gannett Fleming and a former sport fisherman.But this project is different, Saumier says. He takes me to a high bluff and draws with his hands the outline of the new bridge that will free the Santa Margarita.So much going on with the environment is negative these days. We’re building and think we have good intentions, he says.

“A lot of species are going extinct,” Saumier adds. “This time, we’re doing something good for our future.”