Editor’s note: This story was published in the January 2021 issue of San Diego Magazine, and was written when outdoor dining was permitted.

“The floor looks like pavement,” says my daughter. She’s nine, and she’s right. I had to explain to her that here, at this nice restaurant, we are eating in a parking space. Asphalt is the new dining-room floor.

It takes her a minute. She’s disoriented. Aren’t we all.

I didn’t eat at restaurants for four months after the pandemic started. I saw the pain of our restaurant people. I wanted to help, but I was scared. I wanted to support, but I didn’t want to be a reason this spread, a reason someone died. So I stayed home until the science coalesced, until I saw my personal green light to sit on a patio or a parking lot and pay a local chef and tip a local server. To scope out the seating area and mask habits, and make sure my daughter and wife have that famous six feet.

We all have to make our own decisions, read the tea leaves of the daily news. What’s safe, what’s not, what’s responsible, what’s reckless, what’s totally asinine and morally bankrupt. We draw the line, then adjust the line back and forth with each new study and stat. And as I sit here looking at my daughter, I feel safe.

A server at Bencotto prepares gnocchi in a Parmesan wheel.

James Tran

It helps that I spoke with Dr. David Smith, chief of infectious diseases at UCSD School of Medicine. “I think dining outdoors is relatively safe. The biggest issue is who you bring to dinner with you,” he said. “People think, ‘Oh, they’re my friend, they don’t have the infection.’ That’s how bubbles become porous. When it comes to public health, I follow the guidelines. If officials say it’s okay to do something, then I think it’s okay.”

As I write this, outdoor dining is allowed. It’s okay. So I spent three days dining out.

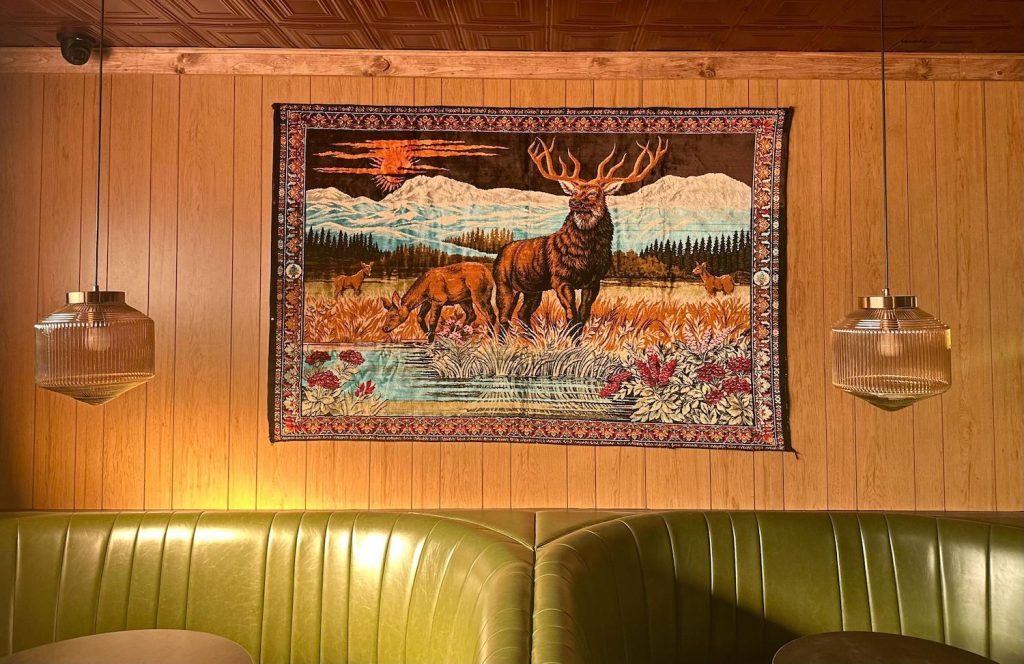

Little Italy is the beating heart of San Diego’s food scene, and the pandemic has given it a murmur. This was ground zero for The Drastic Improvement. High-minded restaurants—Craft & Commerce and Prepkitchen first, then Juniper & Ivy and Herb & Wood later—gutted old warehouses and created food playlands, joining the timeless chorus of longstanding Italian bistros. That alchemy of old blood and new blood created a whole new scene. A heritage zone became a pan-cultural destination. Rent tripled, as did the good times. It’s a place to get octopus and negronis and art and design, a place to selfie and influence.

For me, the experience came down to a bottle of wine. I’m not sure how I saved it. Guess my body momentarily rediscovered fine motor skills, which have grown numb and clumsy from all the doomscrolling. I saw it out of the corner of my eye. It was sliding, picking up speed, making its move for the edge of the table, where it would have taken a swan dive three feet to the asphalt below, shattering and splattering 750 milliliters of very enjoyable cabernet sauvignon onto Date Street. But somehow, I snatched it.

The bottle was sliding because the excellent Italian restaurant Bencotto—like all San Diego restaurants—had been required to move their entire operation into the streets. And the street in front of Bencotto is slanted. It isn’t steep, not alpine by any means. But it slopes just enough that the nine-year-old sitting across from me is at a slightly higher elevation, appearing older and more able to impose her will on my life. Slanted enough that wine bottles occasionally make a run for it.

Filippi’s Pizza Grotto, which has been in Little Italy for 70 years, also adapted its dining service.

James Tran

Many restaurants here in Little Italy are getting a crash course in asphalt hospitality. On June 13, the neighborhood closed its major pedestrian streets to car traffic every Friday and Saturday, granting restaurants more room to reinvent themselves outdoors and creating more space for physical distancing and droplet avoidance. Restaurants turned themselves inside out, building both makeshift and sophisticated alfresco replicas. This experience spread to other parts of the city in August, as officials eased restrictions on “parklets,” allowing businesses to turn parking spaces into dining spaces. Mayor Todd Gloria was one of the early proponents. During his campaign, he told me, “Every time we have reclaimed space from parking and given it back to people it’s been a home run.”

I’m sure Bencotto’s owners don’t resent their incline. They must be glad they’re in popular Little Italy and have enough asphalt to put chairs and tables on, with a few temporary plant-wall partitions for charm. Many restaurant owners across the county aren’t lucky enough to have this kind of outdoor space to expand into. I’m sure Bencotto is grateful their parklet allows them to sell enough Barolo and cacio e pepe to pay enough of the rent, the gas, the electric, and a triage crew of employees until some vaccine or god brings a little mercy and we bid the coronavirus a middle finger. Grateful that in spite of what’s happened to the American restaurant industry during the pandemic, chef Fabrizio Cavallini is still back there layering his lasagna bolognese, which he and his staff have made from scratch every day in this location for 11 years.

As for what happened to the American restaurant industry—Statista created a graph that tracked the year-to-year daily change in “seated restaurant diners.” On February 29, 2020, the industry was seeing a 3 percent increase in customers over 2019. Optimism abounded. From that day on, the graph looks like a capital L. It goes straight south until it flatlines at the bottom. From March 21 through April 30, the restaurant industry was down 100 percent. The graph yo-yos through the fall, depending on how rosy or dark a picture news outlets were painting at the time. But on the very best day for American restaurants since the pandemic started—October 5—they still had 14.9 percent fewer diners than last year. As of press time in early December, the numbers have sunk again to 50 percent of normal business. According to Restaurant Business Magazine, in those darkest days around April, 5.9 million employees lost their jobs. Three decades of growth lost in six weeks. Every industry has suffered. But Google “industries most heavily affected by COVID,” and restaurants will be on every one of those lists.

Apologies for the momentary doomwriting. Point is, given all the perspective we should have by now—most crucially, about the lives lost—who gives a hint of a damn if that wine bottle had exploded? We’d just chalk it up as another punctuation mark in the grotesque run-on sentence that is 2020.

A seafood platter from Ironside’s raw ba

James Tran

But that in and of itself is a point. The barrage of terrible news makes it more difficult for the food-and-drink people—not just owners, but dishwashers, bussers, cooks, bartenders, food truck drivers, farmers, cleaners, brewers, everyone—to find or even ask for a sympathetic ear. Human sympathy is not a bottomless reservoir.

That wine also represents the small guilts of dining out during a pandemic. Guilt that I’m able to afford a restaurant meal, let alone a bottle of decent cabernet, when I know that in May the National Restaurant Association estimated that two-thirds of the country’s restaurant workers had lost their jobs. On the positive side, the bottle is a tangible expression of why I’m here: to support the people and industry I love. And the strongest way to increase the profits of a restaurant, aside from Venmo-ing them extra money, is to order drinks, which provide their biggest profit margin per item by far. The bottle represents the potential dangers of dining out while the virus is still at large and vaccines still just a promise, since we know that a couple glasses mean relaxed inhibitions. And with relaxed inhibitions come improper mask etiquette and loud talking and high fives and—god forbid—hugs or singing.

After spending three days here watching what it’s like for restaurants, I’ve decided: That sliding bottle is everything. It is just another small consequence of trying to be a responsible part of society while also trying to keep your business alive and your people employed. In the past, a broken bottle of wine was just an expected cost of doing business. Now, it’s more straw for the camel’s back. When I look around at Little Italy, every business seems a stalk away.

And so in the parking lot at Filippi’s Pizza Grotto—one of the oldest restaurants in San Diego, where an Italian family sold enough pizza and pasta to ensure a generation or two a decent life—I ate enough pizza and pasta to ensure a few more. A hostess with a firmly attached mask pointed an infrared thermometer at us before granting us a seat. Once cleared, we dined in the night air that smelled of stewed tomatoes and hand sanitizer. We saw the brown spots on the underside of the tent shades—a lesson learned about socially distancing heat lamps from flammable material. Their tables are more spread out than most restaurants I see (possibly because they’ve been here forever and control one of the only big parking lots in Little Italy). Still, I silently judge a table of eight for irresponsibly gathering, and am shamed when one stands to make a toast “to Dad.”

A masked server greets guests at Ironside.

James Tran

At Ironside Fish & Oyster Bar, where the daily bread is biblically good and chef Jason McLeod has earned a reputation for leading the sustainable seafood movement, keeping distance is honestly not as easy. Their sidewalk and parklet are smaller. I stare at the tables and use the mental measuring tape we’ve all developed—always looking for six feet.

We all dine out for different reasons. But since last spring, for me, it’s been a way to role-play normalcy. To listen to the music of forks on plates, of people conversing—not on Zoom, but in a shared physical space. I’ve realized I miss the sounds of restaurants the most. That joyful chaos. The remarkable thing about hospitality people is their ability to normalize the craziness. They make a little theater of it, and an elegance. Even their masks—designer and branded—look aspirational.

As we leave, I watch a vendor pull a wagon full of single roses in cellophane down the middle of India Street. He sanitizes them and sells them. A small band busks in the gutter for passersby. One of them plays a tuba, and I can’t help but envision a mist of corona coming out of his brass funnel. But I look at the small crowd—all spaced apart, wearing masks, being socially responsible—and I see them smile and groove for a brief moment before we all scatter back to our safe spaces. That smile and groove is why we leave the house at all.