The chef’s garden at Fauna greets diners on arrival.

Photo Credit: James Tran and Olivia Beall

Humans die without enough salt. Drink an obscene amount of water and it will flush the salt from your body, creating a potentially fatal condition called hyponatremia. This is why salt has been coveted by pretty much every culture who ever enjoyed being alive. It was used as currency for millennia. The word “salary” comes from salt (money paid to employees so they could afford salt), as does the word “salad” (Romans salted their leafy greens to make their lives taste a little less BC). China supplies the most salt, 68.5 million tons annually. The US is second, creating almost 15 percent of the world’s supply. And the third largest supplier was the kitchen at Fauna the two days my wife, Claire, and I dined there.

Our hands are swollen, our feet are swollen, our swelling is swollen. My blood pressure, if measured, would resemble two impressive pinball scores. It got so dire that, after the first dish of our second meal at Fauna, I pleaded with the server, “No más sal, por favor. Tranquilo con sal, por favor.” In terribly broken Spanish, I begged.

I’ve been reviewing restaurants for over a decade. I’ve been served raw chicken, steak the dead gray hue of a smoldering tire fire, and a “buerre blanc” that I’m fairly certain was just a stick of microwaved butter. But no mistake has ever been as wild and consistently drastic as the 2019 Great Fauna Salt Incident.

I felt—still feel—a need to take partial blame.

Clockwise from top left: Turkey torta ahogada, duck sopes, Bruma Sour cocktail, churro, whole striped bass.

Photo Credit: James Tran and Olivia Beall

I went to Fauna because this Valle de Guadalupe restaurant is a big deal, as is Bruma—its sprawling parent winery and eco-villa retreat. And because Valle de Guadalupe is one of my favorite road trips from San Diego. From downtown, point your car south. Two hours later you arrive in Mexico’s largest wine region—a mile-wide valley of brush and dust and oaks, blessed with a Mediterranean microclimate, winding east into the hills above Ensenada for 20 miles.

The first grapes here were grown in the early 1900s by a Russian sect (who didn’t drink, but were smart enough to sell their fruit to those who did). German scientist Hans Backoff created the first high-end winery, Monte Xanic, in 1988. A decade later, the region gained an ecological and philosophical rudder with Mexico City–born, Bordeaux-trained winemaker Hugo D’Acosta and his Casa de Piedra winery. Aside from Cocina de Doña Esthela and a few others, restaurants here consisted mostly of seasonal campestres (pop-up restaurants) during wine harvest and celebration (called Vendimia).

Then, in 1999, chef Jair Téllez opened the yard-to-table restaurant Laja, which American media, always fans of a good ethnocentric metaphor, referred to as “the French Laundry of the Valle” (Téllez, a plainspoken intellectual, groans at this). Wineries opened one by one, slowly at first. But when it comes to commerce, walking always leads to running.

So after about 2014, the humble Valle had fairly world-class restaurants and wine that, while not amazing, showed that the young growing region was full of promise, getting better with each vintage, and far more drinkable than Temecula.

Valle has remained one of my favorite road trips because some US citizens’ general fear of Mexico has prevented drastic overcrowding. If it were north of the border, it would already be a terrible mess. Yet the number of wineries has tripled in the last six years, to about 120. About 750,000 tourists visit annually. The danger is simple: Developers want to turn Valle into a luxury wine Disneyland with resorts and golf and the usual bells and whistles of affluent playtime; farmers and stewards are fighting them off by pointing at the utter lack of water and saying, “Are you mental?”

Meanwhile, every major American media outlet—the New York Times, Vice, Food & Wine, the Washington Post,CNN, Forbes, Vogue—and every vagabond influencer is telling people it’s the place to go, the chakra-aligning center of life itself. A recent headline from the Sacramento Bee declared, “Valle de Guadalupe a Spring Break Destination for Wine.” The pressure is on, and we’re all complicit.

So Valle needs the right kind of growth, and the locals I spoke with say Bruma is the right kind. Owned by eight childhood friends led by Mexico City developer Juan Pablo Arroyuelo, the hotel is designed to be almost indistinguishable from its natural surroundings. It’s barely visible from the main road, Ruta del Vino. We enter through a 15-foot-tall gate—guarded by two very friendly men, one with a holstered gun who leads us on his ATV through an olive-tree-lined dirt road toward our accommodations. The road gets rough, largely engineered by wind and rain, full of ruts and warranty-voiding dips.

I’m reminded of when D’Acosta told me five years ago, “Good roads, bad tourists. Bad roads, good tourists.” Ideally, the Valle will never be fully paved or easy.

The turkey torta ahogada is doused in broth

Photo Credit: James Tran and Olivia Beall

Bruma and Fauna were designed by D’Acosta’s brother Alejandro, an architect, and it’s a marvel of how to build beautiful things from unwanted things. Most of the raw materials were found on the side of the road or in the nearby hills. A man was hired just to find “high-quality garbage,” which was then treated for durability and used in construction. Modern, airy, industrial studios are nestled low, almost into the ground, as if you’re sleeping in a giant, benevolent, burrowing animal. Two dogs, Lala and Abby, greet visitors and come along for the tour and chase sticks under a giant oak tree that centers things. A woman explains that since it’s a Monday in December, occupancy is low and she can upgrade us to a suite free of charge.

Overlooking an artificial lake you can swim in, the suites have a large shared patio with a long, heated plunge pool. A frog croaks. Hawks circle above. The late afternoon light is so soft it looks like a mist of electrons or low-wattage fireflies, as the sun sets gaudily on the west end of the Valle.

Our room has a private outdoor stone bathtub and a double-headed shower with floor-to-ceiling windows. It’s a nice place to practice the exhibitionist arts. A study nook juts off the room like a sidecar, surrounded by windows gazing out on the miles of vineyards. Four suites share a common area made of wood, iron, stone, and sex appeal. With perfect mood lighting and 30-foot ceilings, it looks and feels like you’ve wandered onto a Dwell magazine photo shoot. Reclining on the linen couch before the wood-burning fire (catered to by a personal attendant, who will also cook breakfast from scratch in the morning), you can read provided art and design books, write, or just look pensive and deep. Structures like this make the most ab-deficient among us feel like bohemian supermodels. I’m not sure if Bruma was made for Instagram or if Instagram was made for Bruma.

A hundred yards past the lake, tucked into a hill, is the winery. It appears almost dinky from the outside, but don’t be fooled—80 percent of it is underground. The natural cellar controls temperature of the wines, initially overseen by Hugo D’Acosta and now by heralded young winemaker Lulú Martinez. Atop the winery, what appears to be a personal-size lake with a fossilized tree in its center is actually a “mist isolation system,” designed to harvest morning dew, regulate temperatures inside the winery, and prevent evaporation (a much-needed innovation for a water-poor region). Underground, tiny circular windows turn out to be eyeglass lenses “rescued” from a local optometry warehouse. The wood was salvaged from a demolished bridge in San Francisco.

The tree outside Fauna

Photo Credit: James Tran and Olivia Beall

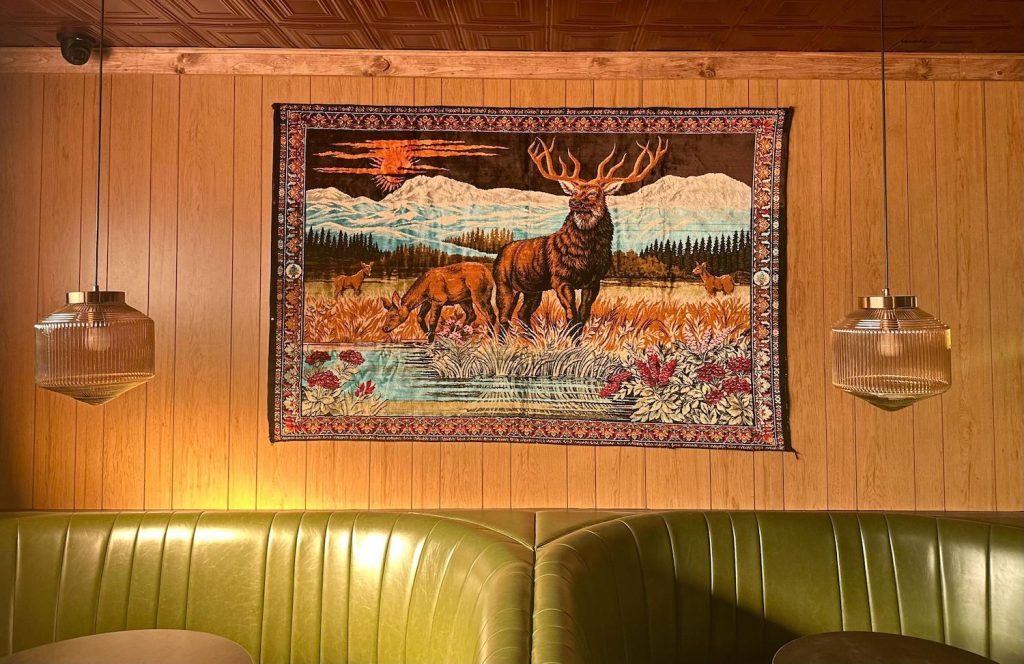

Next door is Fauna, a single wood-and-steel dining room with two massive communal wooden tables inside, and two outside on the dirt patio (shaded with the help of 30,000 sticks they rummaged from surrounding bush, naturally). Most of the guests in Fauna are Mexican, well-dressed and seemingly tossing their hair in slow motion, with good teeth and intelligent eyes that have analyzed a NASDAQ index or two in their day. A large garden out front grows much of the produce used by chef David Castro Hussong and his wife, pastry chef Maribel Aldaco Silva. An outdoor kitchen smokes local meats; an indoor performance kitchen handles the rest.

Taken together, all three structures—the villas, winery, and restaurant—are one of the most magical, naturalist compounds I’ve ever stood in or dreamt of. Bruma and Fauna are breathtaking.

Now, back to our meals. Driving out of the Valle back toward the US border, I felt I’d done an injustice to one of my favorite regions in the world.

And here’s why. The only days I had available to visit Fauna for this review were a Monday and Tuesday—which are often days off for chefs. On both days the kitchen was without Hussong—grandson of the man who created the famed Hussong’s Cantina, who cooked under Dan Barber at Blue Hill at Stone Barns and Daniel Humm at Eleven Madison Park, took a brief stint at Noma, had his face recently featured on the cover of Food & Wine en Español magazine.

Sopes being made on the outdoor comal (grill)

Photo Credit: James Tran and Olivia Beall

Is it fair to review a restaurant when its heralded captain isn’t present, taking an overdue respite, reminding his body what sleep is? I considered postponing, and returning when he was in the kitchen.

After hours of discussion with Claire and colleagues, I decided it was fair for one simple reason: Fauna was open. The diners who’d traveled to eat there—like the Canadian couple who’d driven a half hour across the valley from their winter home—were paying customers. Though criminally less expensive than American restaurants of its caliber (most great Mexican restaurants are), there was not a “chef’s day off” discount. And the plain fact is, whoever was in charge those two days made weapons of salt and lemons.

It’s such a shame, and I don’t think it’s representative of the Fauna experience. The staff was excellent and knowledgeable and patient with my ramshackle Spanish. The wines—a Bruma Casa Ocho Chardonnay, and a 2017 Tinto Cabernet Sauvignon—were balanced, with enough backbone and flower. And you could see the clear, skilled vision of each dish, the balance of textures and colors, wild ideas and comfort-food techniques, the super-fine cuts of herbs, the light touch of the deep fryer, the artful plating.

The first bite we had was of a pozole-like soup, filled with pork cubes, oregano, and blue corn fried so that it puffed up to resemble tiny mushrooms. It put every grandmother’s soup to shame, food as a soul blanket. The second dish, an oyster taco, was a delicate leaf of cool lettuce filled with shredded zucchini cactus and topped with an oyster perfectly fried. But here’s how this dish—and almost every dish after it for two days—went: First we taste the flavors of the ingredients, and they’re truly great, then our excitement recoils as the salt and acid hit a second or two afterward, like aggressively bad medicine, almost inedible. Our palate is toast.

The patio at Fauna

Photo Credit: James Tran and Olivia Beall

With the cooking style that Hussong has his kitchen operating in—namely, bright with high acidity—there is very little room for error. High salt plus high acid, done even barely wrong, can taste like leaky batteries in your mouth.

Hussong’s menu rotates constantly, dictated by seasons and his garden. You can order à la carte, but it makes the most sense to do the Fauna Feast, which gives you a sampling of nearly the whole menu—an incredible bang for the buck. We Feasted both days, and a few dishes escaped the Salty Acid Event, showing how excellent Fauna can be. Like the turkey torta ahogada—a Jalisco specialty, where the sandwich is drowned in broth—white bread toasted and open-faced, topped with layers of juicy roasted bird, cauliflower, asparagus, and pickled onions. It’s a Baja French dip of sorts. Duck sopes, while teetering on the acid brink, are lovely with their puffy base of blue corn (the sope itself, which is similar to an English muffin), tufts of duck confit, avocado crema, and lettuce from the garden. Or the whole striped bass, served with crispy skin and still in full swimming form. They smartly don’t fuss with this, serving it with salt, olive oil, lemon, and a mildly spicy red pepper sauce. Our one dessert is a delicious, warm churro wrapped around Ramonetti cheese.

The Bruma Sour with yellow chartreuse and egg whites, topped with dehydrated orange and sage

Photo Credit: James Tran and Olivia Beall

Later in Bruma’s common area, a man overheard Claire and me discussing the salt dilemma and chimed in. He agreed. Thank god, because I was wondering if something was wrong with our mouths. I also asked a friend for their opinion, and without prompting they replied, “Beautiful, but way too much citric acid.” Other food people I respect were shocked to hear about our experience, and say they’ve had nothing but brilliant meals there.

Hussong undeniably has the talent. I’m just not sure the kitchen has the strength yet to do it without him. Based on the ideas of the dishes, and the awesome flavors before the flood of salt and lemon, I’d go back. Bruma and Fauna are, on design and vibe and ethos alone, an instant favorite place to be alive.

I’d just call to make sure the chef is in.